Korea

Joseon (15th Century)

Towards the end of the 14th century, Goryeo found itself in a difficult situation due to internal and external problems, including a struggle for power among the nobility and incursions by Red Turban rebels from China and Wako pirates. At that time, General Yi Seong-gye had become popular among the people for his role in driving away foreign invaders. He overthrew the Goryeo dynasty and founded a new dynasty, Joseon. As the first King Taejo of Joseon, he chose Hanyang (present-day Seoul)—judged to be a propitious spot according to the principles of feng shui—as the capital of the new dynasty. He also ordered the construction of Gyeongbokgung Palace and the Jongmyo shrine, as well as roads and markets. The new capital, located in the center of the Korean Peninsula, was easily accessible via the Hangang River, which flowed directly through its heart.

King Taejong, the third king and son of the founder of the dynasty, made a significant contribution to stabilizing the centralized system of governance. He adopted a system under the law of hopae (identification tags) to determine the population, and launched the major executive bodies called the Six Ministries of Joseon: Personnel (Ijo), Taxation (Hojo), Rites (Yejo), Military Affairs (Byeongjo), Punishments (Hyeongjo), and Public Works (Gongjo), all of which had to report directly to their king. King Sejong, the fourth king and a son of King Taejong, ushered in an era of great political, social, and cultural prosperity. Scholars at the Jiphyeonjeon (Hall of Worthies) developed strong and effective policies. During the reigns of Sejo, Yejong, and Seongjong, the Gyeongguk daejeon (National Code) was drawn up with the aim of establishing a long-lasting ruling system.

The Creation of Hangeul

Koreans had used the Traditional Chinese characters for a writing system for many centuries. Idu and Hyangchal, systems for writing the spoken word, using Chinese characters, had been developed, but they left much to be desired. Hangeul (the Korean alphabet), was created by King Sejong in 1443 and was promulgated as the national writing system in 1446. The shapes of the Korean alphabet were based on the shapes made by the human vocal apparatus during pronunciation. Many scholars have stated that Hangeul is the most scientific and easy-to-learn writing system in the world. It contributed to drastically enhancing communication between the people and the government, and played a decisive role in becoming a culturally advanced country.

Development of Science and Technology

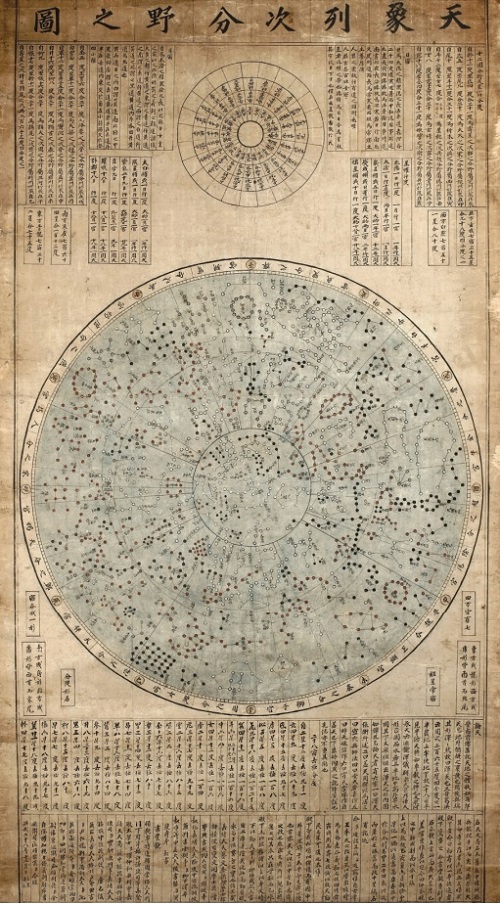

During the Joseon period, the country’s science and technology developed remarkably. The Jagyeongnu (clepsydra), Angbuilgu (sundial), and Honcheonui (armillary sphere) were all invented in the early period of the dynasty. A rain gauge, the first of its particular kind in the world, was used to measure precipitation. Devices for land surveying and mapmaking were also made. During the reign of King Taejo, the Cheonsang yeolcha bunya jido (Celestial Chart) was made based on a previous version drawn up during the Goguryeo period. During the reign of King Sejong, Chiljeongsan (meaning the calculation of the motions of the seven celestial determinants) was made on the basis of the Shoushili calendar of China and the Islamic calendar of Arabia. Noticeable advances were made in the sphere of medical science. Hyangyak jipseongbang (Collection of Native Prescriptions for Saving Lives) and Uibang yuchwi (Classified Collection of Medical Prescriptions) were compiled regarding Korean native medicines, and treatments. Metal printing types, such as Gyemija and Gabinja, were making it possible to publish many books.

Angbuilgu (Joseon, 17th-18th Centuries) (Left)

A sundial capable of marking changes in both time and season

Rain Gauge Support (Joseon, 18th Century)

Rain gauge support in Seonhwadang, Daegu, on which a rain gauge is put to measure rainfall

Cheonsang Yeolcha Bunya Jido (Late Joseon)

This astronomical chart from Joseon shows the constellations.

Joseon’s Foreign Relations

Joseon maintained friendly relations with the Ming dynasty of China. The two countries exchanged royal envoys every year and engaged in busy cultural and economic exchanges. Joseon also accepted Japan’s request for bilateral trade by opening the ports of Busan, Jinhae, and Ulsan. In 1443, Joseon signed the Gyehae Treaty with the clan of Tsushima Island for limited bilateral trade. and Joseon also traded with other Asian countries such as Ryukyu, Siam, and Java.

Development of Handcraft Skills

Ceramic ware is perhaps the most representative handcraft of the Joseon period. Grayish-blue-powdered celadon or white porcelain was widely used at the royal court or government offices. By about the 16th century, Joseon’s Ceramic ware production skills had reached their zenith. Its white porcelain typically exhibited clean, plain shapes based on the tradition established during the Goryeo period. They were suited to the aristocratic taste of the Confucian scholars.

White Porcelain Jar with Plum, Bamboo, Bird Design (Joseon, 15th Century)

This vase made in the early Joseon period displays a uniquely Korean atmosphere in its refined portrayal of bamboo, plum, and birds.

Imjin Waeran (Japanese Invasion of 1592)

Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, Joseon maintained good relations with Japan. In the 16th century, however, Japan called for a larger share of the bilateral trade, but Joseon refused to comply with the request. The Japanese threw the Joseon society into turmoil by causing disturbances: the Disturbance of the Three Ports, also known as Sampo Waeran, in 1510 and Eulmyo Waebyeon (Japanese pirates’ disturbance) in 1555. In Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi brought the 120-year-long Sengoku period (Age of Warring States) to a conclusion and unified the country. Then, in 1592, he invaded Joseon with around 200,000 troops, with the aim of dissipating local lords’ strength and stabilizing his rule in Japan. The war lasted for seven years until 1598, which is called the Japanese invasions of Korea of 1592–1598 or Imjin War.

Feeling threatened by the invading Japanese troops, King Seonjo of Joseon fled to Uiju, close to the Ming dynasty, and asked Ming to come to his aid. The Japanese invaders marched into the northern provinces of Joseon. Korean militias started fighting against the invaders here and there across the country. It is particularly noteworthy that Korean naval forces led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin won one victory after another against the invaders and defended the nation’s breadbasket in Jeolla-do, and thus blocked the Japanese supply lines, thereby demoralizing the Japanese army. The Japanese forces pulled out of Korea, but invaded Joseon again in 1597. Although Admiral Yi Sun-sin was left with only thirteen warships, he won a devastating victory against the Japanese fleet of 133 ships. The sea battle waged in the Strait of Myeongnyang was one of the greatest military engagements of all time.

Following the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the Japanese invaders returned home. During the seven-year war, many cultural properties in Joseon, including Bulguksa Temple, were destroyed. The Japanese took away books, printing types, and works of art from Joseon. With these spoils of war, the Japanese were able to enhance scholarship and the arts in their own country, while potters whom the Japanese troops abducted from Joseon helped Japan develop its own china culture.

Development of Grassroots Culture

In the late Joseon period, commerce and industry entered a period of rapid development. Many children could receive education at private schools in their local neighborhood. With these improvements in the quality of life of the people, they began to enjoy diverse entertainments. Stories written in easily understood Hangeul, as opposed to literary works published in Chinese, were widely distributed. Pansori (a genre of musical storytelling) and mask dances developed into the representative genres of the grassroots culture. In the late 19th century, Sin Jae-hyo adapted and rearranged pansori saseol (stories), which is today called the five madang of pansori: Chunhyangga (Song of Chunhyang), Simcheongga (Song of Sim Cheong), Heungboga (Song of Heungbo), Jeokbyeokga (Song of Red Cliff) and Sugungga (Song of the Rabbit and the Turtle). In addition, masked dance-dramas such as tallori and sandaenori enjoyed great popularity among ordinary people.

Sandaenori

This is a regional variant of Korean mask dance drama, in which masked actors and actresses engage in witty jokes, dances, songs, etc.